Mapping Communities

Black Enclaves in New York City from 1825 to 1950

in partnership with the dubois Challenge team

Dedicated to the history of Seneca Village and Weeksville, Mapping Communities: Black Enclaves in New York City from 1825 to 1950 is an interactive exploration of these two historic Black communities’ significant contributions to developing New York City’s cultural richness using narrative, timeline, videos, and curriculum.

Through a collection of articles, photographs, and interactive resources, we hope to shed light on the lives of Seneca Village and Weeksville residents and the challenges and opportunities they faced as growing communities in their quest for equality and justice.

The data science used to supplement the rich history of these Black enclaves will fortify these narratives and help quantify and trace the impact of Black communities and how their similarities and differences shaped the “City that never sleeps”.

These narratives build on well-documented studies of Black migration in the US and examine the contexts of Black life in national and global contexts during this time.

Join us on this journey of discovery as we explore the rich and complex history of two of New York City’s most fascinating communities.

But first,

how did these enclaves come to be?

Let’s take a walk through time…

The road to emancipation

1730-1830

It's the Mid 18th Century

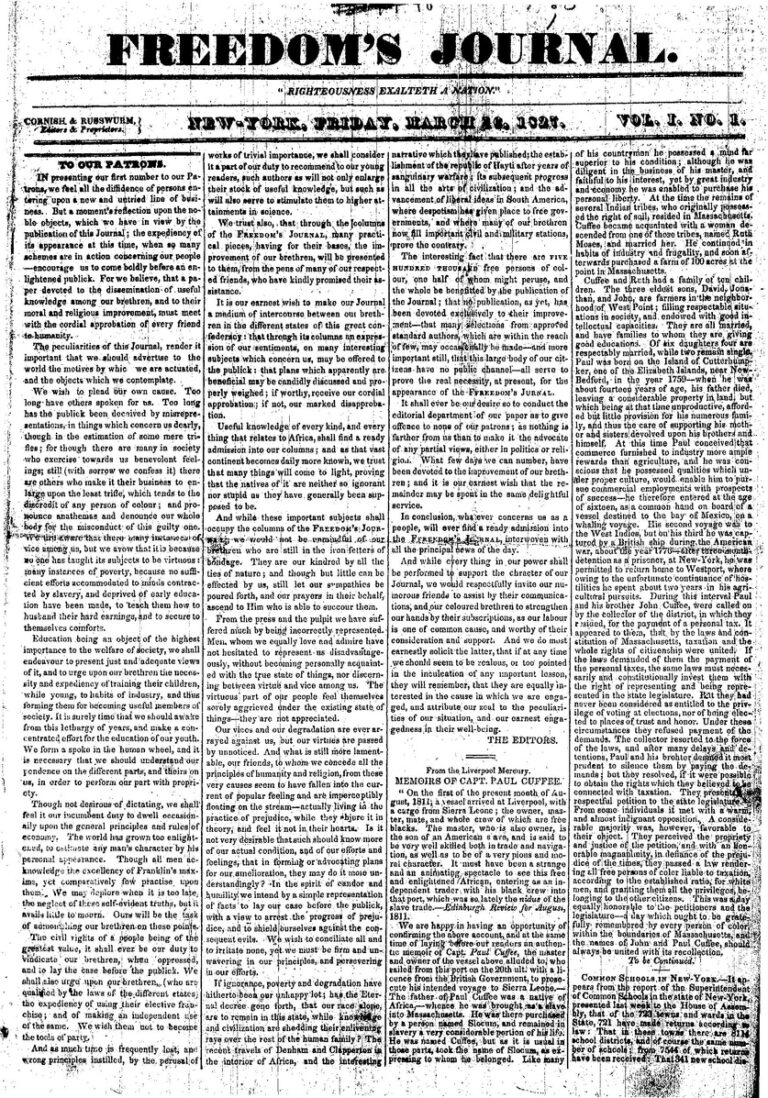

New York City was also a major center of culture and learning. The city had several newspapers, including the New-York Gazette and the New-York Weekly Journal, and it was home to a number of libraries and museums. The city also had many theaters which staged plays from all over the world.

The mid-18th century was also a time of political upheaval for New York City. The city, divided between Loyalists, who supported the British Crown, and Patriots, who supported independence from Britain, became the site of several major battles during the American Revolutionary War, including the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776 and the Battle of Long Island in 1778.

After the war, New York City became the capital of the United States. The city continued to grow and prosper in the 19th century, eventually becoming the largest city in the United States.

Tontine coffee house by francis guy, ca. 1797 depicting manhattan a few years before the process of emancipation began

roughly 20% of nyc’s population were enslaved people

This was second in the country to Charleston, SC.

- Free Population

- Enslaved Population

POPULATION OF NEW YORK IN 1730

POPULATION OF NEW YORK IN 1730

BUT STARTING IN 1799, THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY BEGINS

The Law states that enslaved people born after July 4, 1799, must be freed beginning in 1824.

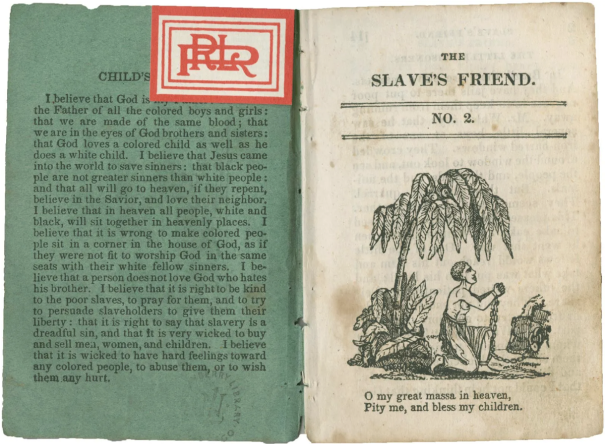

An oration commemorative of the abolition of the slave trade in the United States: delivered before the Wilberforce Philanthropic Association, in the City of New York on the January 2, 1809

The Slave Trade was made illegal.

An oration commemorative of the abolition of the slave trade in the United States: delivered before the Wilberforce Philanthropic Association, in the City of New York on the January 2, 1809

The Law states that enslaved people born before July 4, 1799, must be freed by 1827.

An oration commemorative of the abolition of the slave trade in the United States: delivered before the Wilberforce Philanthropic Association, in the City of New York on the January 2, 1809

NEW YORK STATE CONSTITUTION GRANTED BLACK MEN WITH AT LEAST 200 IN REAL ESTATE HOLDINGS THE RIGHT TO VOTE.

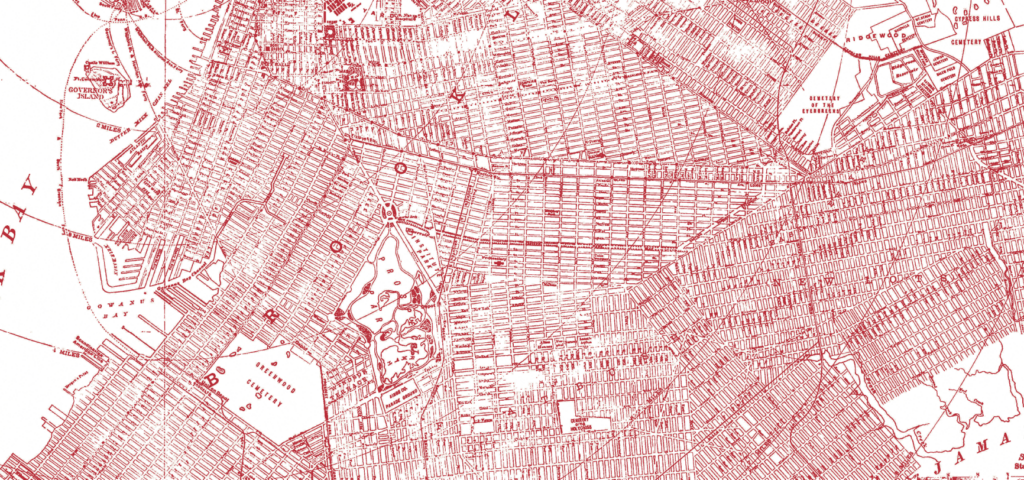

By 1830, Black enclaves are forming in Brooklyn and Manhattan

NEW YORK'S BLACK ENCLAVES

Seneca Village & Weeksville

Seneca Village was a predominantly African American community that existed on the outskirts of Manhattan in the mid-19th century. Despite facing discrimination and marginalization, the community thrived and grew to include schools, churches, and businesses. Unfortunately, Seneca Village was destroyed in the 1850s to make way for the construction of Central Park, displacing its residents and erasing much of its history.

In the 1830s, Weeksville, emerges as a free Black community in the current-day neighborhood of Crown Heights in Brooklyn. Founded by James Weeks and a group of free Black men, Weeksville quickly grew into a thriving community of Black entrepreneurs, activists, and artists. Weeksville continued to flourish even after the Civil War and is now recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

So,

What was the fate of these black enclaves?

Let’s explore

FROM THEN TO NOW

1830 – 1950

- OVERVIEW

- 1834: Anti-Abolitionist Riots

- 1862: emancipation proclamation

- 1863: new york city draft riots

Antebellum and beyond

Overview

As Black New Yorkers became emancipated from slavery, their fate became more divisive. Slavery was diminishing in America, and the industrial revolution began blooming. At the same time, European immigrants were coming to America for a better way of life. Class conflicts erupted between white Americans, emancipated Black Americans, and European immigrants. In the decades following the Civil War, Black New Yorkers continued to face discrimination and violence, including the 1863 Draft Riots, in which mobs of mostly white working-class people attacked Black residents and destroyed their property.

Antebellum and beyond

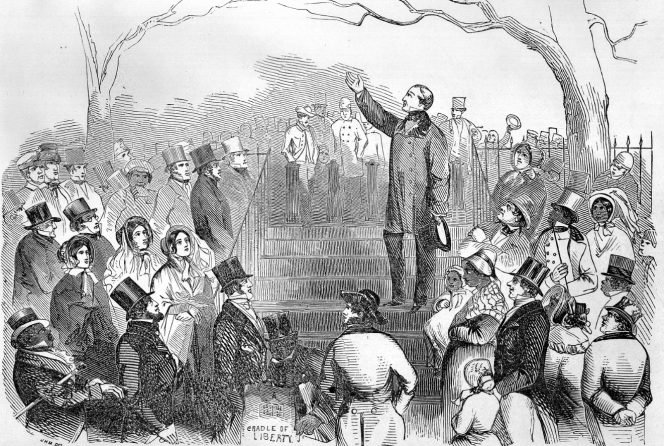

1834: anti-abolitionist riots

These riots lasted for about 7 days until quelled by military force. Growing fear and resentment of Black residents among the growing underclass of Irish immigrants had been brewing. The tipping point was a misunderstanding that took place at Chatham Street Chapel. An integrated group had planned to celebrate the emancipation of slavery in New York. Another group showed up to use the space, not realizing the owners had granted the space to another party. This caused a huge brawl and rumors began to fly that “gangs of Blacks” were going to retaliate. Rioters attacked homes, businesses and churches of abolitionist leaders and ransacked Black neighborhoods. In addition to these events, the mob targeted homes, businesses, churches and other buildings associated with the abolitionist movement as well as those of African Americans. More than seven churches and a dozen homes were damaged. Rioting was hardest in the Five Points neighborhood.

Antebellum and beyond

1862: emancipation proclamation

United States President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, and on January 1, 1863, it became finalized. Officially known as Proclamation 95, it was a Presidential proclamation and an executive order issued by the United States changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free.

Antebellum and beyond

1863: new york city draft riots

Monday morning, July 13, 1863, thousands of white workers, mainly Irish and Irish Americans started attacking military and government buildings. They became violent to those who stood in their way, including police officers and military personnel. By the afternoon, the angry mob targeted Black citizens. In total, there were 119 reported deaths; however, estimates count the death toll around 1,200. The aftermath of the Draft Riots resulted in millions of dollars of property damage forcing 3,000 of NYC’s Black residents into homelessness.

1950 - TODAY

During the mid-20th century, the Civil Rights Movement brought renewed attention to issues of racial inequality in New York City and across the United States. Black residents of New York City were heavily involved in the movement and played key roles in organizing protests and advocating for change.

In recent years, Black New Yorkers continued to face challenges related to housing, education, and police brutality while contributing significantly to the city’s cultural and political life shaping the city’s identity and future.

ABOUT MUSEUM HUE

Museum Hue, founded in Brooklyn, New York, in 2015 by two Black women, continues to be a Black-women-led organization. With an entire staff of Black women. Our membership varies in identity, and notable Black arts and cultural leaders and organizations are members, including The Studio Museum in Harlem, Weeksville Heritage Center, the Jackie Robinson Museum, and many others across the US. Museum Hue’s board historically reflects Black leadership, with the Board always being more than 50% Black. The Black leadership on the board currently includes Mikhaile Solomon, (Board Chair) Founder and Director of Prizm Art Fair, the biggest art fair in the US centering Black artists based in Miami, and Melanie Adams, Director of the Anacostia Community Museum, the first Black Smithsonian located in Washington D.C.

Museum Hue’s founders built the organization from the understanding that Black stories and experiences in the arts field remain central to our work, approach, and pedagogy. Although there are many intersectionalities with other communities of color, Black people’s history, interests, experiences, oppressions, and needs can differ from these communities. Our first program at the Metropolitan Museum of Art with their first Black Chair of Education focused on anti-Blackness in the Egyptian galleries and Egyptology studies.

Let’s continue the conversation

We hope that this project is a resource that can grow with our community. If you’d like to share your thoughts on the narrative we’ve collected here, please reach out to us. We also invite you to get to know us better at our Museum Hue website.